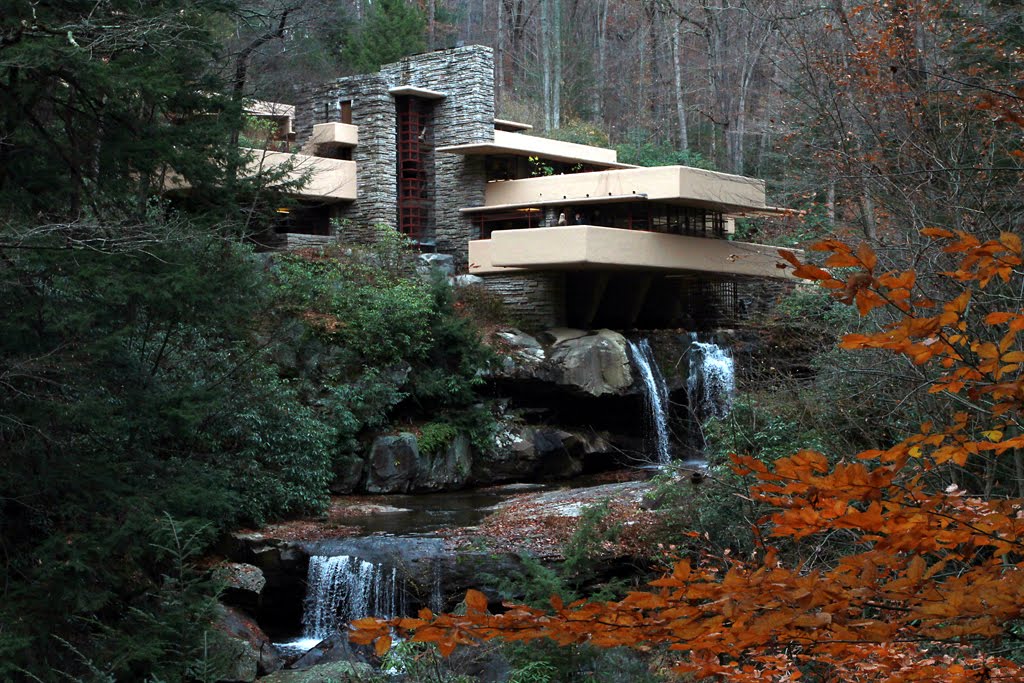

“There in a beautiful forest was a solid, high rock ledge rising beside a waterfall, and the natural thing seemed to be to cantilever the house from that rock bank over the falling water.” Frank Lloyd Wright in an interview with Hugh Downs, 1954.

A most sublime integration of architecture and nature, Fallingwater nestled among the rocky woodlands of Pennsylvania is the focal point for every discussion of Frank Lloyd Wright’s inspired siting, use of organic materials, and employment of decorative motifs derived from nature and translated into glass, stone, and wood.

The construction began in 1936 was finished in 1939. The building is revolutionary and iconic for its bold horizontal and vertical lines built over a running waterfall.

Wright was nearing seventy, his youth and his early fame long gone, when he got the commission to design the house. It was the Depression, and Wright had no work in sight. Into his orbit stepped Edgar J. Kaufmann, a philanthropist with the burning ambition to build a world famous work of architecture. The two men collaborated to produce an extraordinary building of lasting architectural significance, that brought international fame to them both and confirmed Wright’s position as the greatest architect of the twentieth century.

Fallingwater Rising shows how E. J. Kaufmann’s house became not just Wright’s masterpiece but a fundamental icon of American life. One of the pleasures of the book is its rich evocation of the upper crust society of Pittsburgh; Carnegie, Frick, the Mellons. A society that was socially reactionary but luxury loving and baronial in its tastes. Key figures include Frida Kahlo, Albert Einstein, Henry R. Luce, William Randolph Hearst, Ayn Rand, and Franklin Roosevelt.

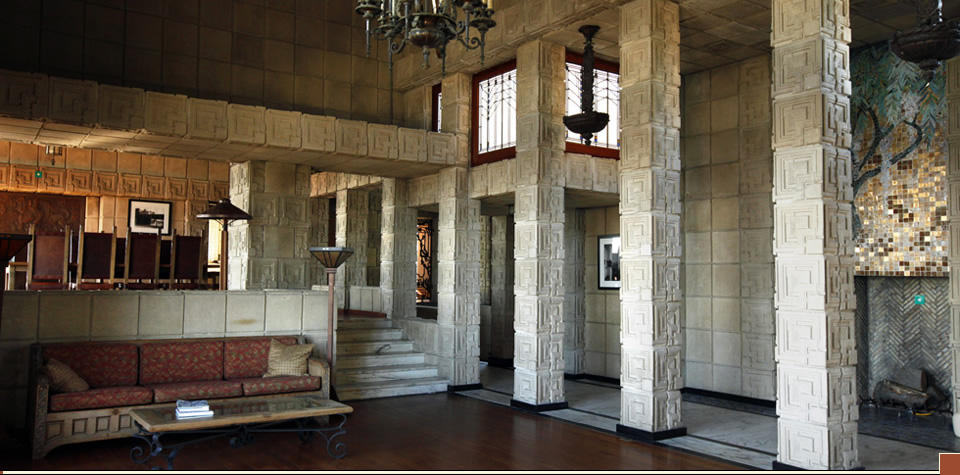

Fallingwater is the only major Wright designed house to open to the public with its furnishings, artwork, and setting intact.